Joseph Pennell

Joseph Pennell | |

|---|---|

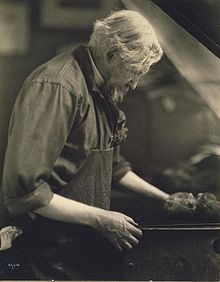

Pennell working at a printing press in 1922 | |

| Born | July 4, 1857 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 23, 1926 (aged 68) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Studied with James R. Lambdin and Thomas Eakins |

| Known for | Etcher, draftsman, lithographer, book and magazine illustrator, author |

Joseph Pennell (July 4, 1857 – April 23, 1926) was an American draftsman, etcher, lithographer, and illustrator for books and magazines.[1] A prolific artist, he spent most of his working life in Europe, and developed an interest in landmarks, landscapes, and industrial scenes around the world.[1] A student of James Lambdin and Thomas Eakins, he was later influenced by James McNeill Whistler.[2] He was married to author Elizabeth Robins, and he also was a writer.

In 1914, he published The Jew at Home: Impressions of a Summer and Autumn Spent with Him (1892) followed by photo-documentary works including Lithographs of War (1914),[3] Pictures of the Wonders of Work (1915),[3][4] and The Adventures of an Illustrator (1925).[5] In later life, he and wife Elizabeth both wrote art criticism and co-authored books.

Early life and education

[edit]Pennell was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on July 4, 1857. He was raised by his Quaker parents, Larkin Pennell and Rebecca A. Barton. At age ten, the family moved to the Germantown section of present-day Philadelphia, where he attended The Friends Select School "for six awful years, the worst of my life", a loner with few friends.[6] Pennell spent much of the time drawing, a skill not praised in his school. He received drawing lessons from James R. Lambdin.[2]

Career

[edit]After attending The Friends School, Pennell worked in an office of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company. His application to the new Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts was rejected in 1876; instead, he studied at the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art by night until he was expelled in 1879 (Pennell claimed for encouraging a mutiny among the students). His School of Industrial Art professor, Charles M. Burns, who had recognized Pennell's ability, helped gain him entry to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he studied under Thomas Eakins and others. Pennell's talents lay in graphic arts, rather than painting, and his abrupt personality contributed to difficulties during his years at the academy.[2]

In 1880, Pennell was involved in the violent expulsion of African American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner, a fellow student, from the academy. Tanner had suffered bullying at the academy since his entry earlier that year, which culminated when a group of students including Pennell seized Tanner and his easel and dragged them out onto Broad Street. The students tied Tanner to his easel in a mock-crucifixion, and left him struggling to free himself. Pennell apparently did not regret this action; many years later, when Tanner was already renowned in Europe and beginning to gain repute in the United States, Pennell recounted the attack as "The Advent of the Nigger," writing that there had never been "a great Negro or a great Jew artist."[7]

Pennell was determined to work as an artist and opened his own studio in 1880, which he shared with a Henry R. Poore. Like his later mentor, James McNeill Whistler, he also left America for London, England, on a commission to provide illustrations for US Century magazine, and taught at Slade School of Art. He won a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle (1900), and 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. He taught also at the Art Students League of New York.[1]

Joseph Pennell's Pictures of the Wonders of Work is a 1915 publication featuring 52 of Pennell's images, from around the world over three decades, with an introduction by the artist and detailed biographical work notes. It serves as an excellent and insightful summary of his career up to that point, and is freely available as an e-book;[4] As is Pennell's 1925 The Adventures of an Illustrator:[5]

In a productive career as an artist, Joseph Pennell made over 1800 prints, many as illustrations for magazines and books of prominent authors. Depicting first landmarks of his native Philadelphia, USA, then travelling the globe and back recording the landscapes of South America, mainland Europe and industrial cities of his adopted English home. His distinction is as a highly talented original etcher and lithographer and illustrator, a writer, influential lecturer and critic. As Mahonri Sharp Young writes:

[Y]oung Pennell had a genius for not getting along with people yet was immediately successful in the fiercely competitive field of illustration. Hard working with remarkable ability and specific talent for drawing, he produced a tremendous volume of highly regarded work. He offended many, but knew everybody, including the most talented.[6]

As captain of the Germantown Bicycle Club, early work included illustrations for cycling articles. After studying at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Pennell opened his own studio in 1880, shared with another artist, and was successful from the start, getting commissions from Harper's and Scribner's (later The Century Magazine) and other publications. He also worked in New Orleans as a book illustrator,[8] and made sketches and watercolours of the Bethlehem Steel works, just north of his native Philadelphia.[9]

In 1883, he was sent by Century to Italy, to work on illustrations for a series of articles by William Dean Howells. It was here Pennell created his 'first etching made in Europe' of The Ponte Vecchio, Florence,[10] recalling in his 1925 book The Adventures of an Illustrator:

I went to Italy to make my etchings and they were what I cared for. All day and every day I worked at them, drawing them straight on the plates, and that is why they and other proofs by etchers who draw from nature on the copper are reversed in printing. I even tried to bite them out of doors as I drew them – Hamerton' Philip Gilbert Hamerton- 'had recommended that – but only once, for I could not see and I swallowed the fumes of acid as I bent over the flat easel which held the bath, and then I upset that.. but the crowd enjoyed it, especially when the fumes ate the skin off my throat and I spat blood all about'[11]

That same year Pennell produced a series of evocative illustrations of heavy industry in Northern England, capturing Sheffield 'Steel City' as the world renowned centre of steel production, with all the shadowing heavy pollution that came with it. The Great Stack, Sheffield[12][13] and the later dated The Big Chimney, Sheffield[14] Pennel later commented; 'I may say that in 1883 I made a series of illustrations of work subjects in Sheffield which were printed in Harper's Magazine. Two things always impressed me in that town—the boiling water in the rivers and the abominable habits of the natives in the streets, who from across the rivers and behind walls and other safe places "'eave arf a brick" at you if you dare to draw.'[4]

Relocation to England

[edit]

In 1884, he received a major, and life changing, commission from Century Magazine, a long-term assignment to produce drawings of London and Italy, plus English and French Cathedrals – this necessitated Pennell and his wife, the writer Elizabeth Robins Pennell, relocating from America to a new home in London, England, establishing Pennell as an Anglo-American Artist and introducing them both to new connections such as writers H. G. Wells, Robert Louis Stevenson, Henry James, George Bernard Shaw and painters John Singer Sargent, William Morris and James McNeill Whistler – the latter had a profound influence on Joseph Pennell, and when Whistler moved to Paris in 1892, Pennell followed in 1893 and spent a period working with Whistler in his studio.[2]

The Pennells readily engaged with London's literary and artistic circles, co-authoring articles and books detailing their European travels, including Two Pilgrim's Progress, an 1886 illustrated book of their journey from Florence to Rome riding a heavy tricycle, and a 1906 biography of James McNeill Whistler, not published until 1908 due to litigation with Whistler's Executrix over whether it had been authorised by Whistler and whether the Pennells had the right to use the Whistler letters they had collected. The Pennells won the lawsuit, but not the rights to publish the letters. [2][15]

In 1887, Pennell began writing as Art Critic for The Star in London, a column originally started by George Bernard Shaw, but Pennell's outspokenness upset both the academy and other artists, and the editor asked Elizabeth Pennell to step in and contribute, launching her career writing art criticism.[2][15] Joseph Pennell was also elected a committee member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers and his growing renown as a graphic artist won commissions for book illustration.[16] 1889 found Pennell in France, sketching 'The devils of Notre Dame' – stone gargoyles of the Paris Cathedral. One of these pen drawings was printed in the London Pall Mall Gazette[11] By 1901 he was working with William Dutt providing illustrations for his book Highways, Byways and Waterways of East Anglia : a Collection of Prose Pastorals

Pennell returned to the United States in 1904, producing a series of striking New York images marking the dramatic change that new development, like the Flatiron Building, the Times Building and the many towering skyscrapers still under construction, were making to the Manhattan skyline. This work was published in both American and British magazines, and Pennell returned to document New York in 1908.[16]

He made further trips to the Americas, including to San Francisco in March 1912, where he undertook a series of "municipal subjects" which were exhibited December 1912 at "the prestigious gallery of Vickery, Atkins & Torrey".[17] It is quite possible that Pennell's visit inspired San Francisco printmakers Robert Harshe and Pedro Lemos, along with sculptor Ralph Stackpole and painter Gottardo Piazzoni, to found the California Society of Etchers in 1912, now the California Society of Printmakers.[18]

That same year Pennell also traveled to Panama to create lithographs of the Panama Canal, which was still under construction.[19] Steam Shovel in the Cut at Bas Obispo[18]

After spending part of 1914 in Berlin, Pennell made it back to London just as World War I was declared, and obtained permission from the British PM David Lloyd George to record the war effort, sketching munitions factories in North England; Turning of the Big Gun at Vickers Sheffield[10] The Big Bug,[3] From the Tops of the Furnaces.[20]

While sketching a Leeds munitions factory, Pennell recalled encountering a hostile crowd and having to escape with help from the local police. He reflected; "Why does war make people so idiotic, why do people fear an artist more than an enemy. Art is powerful and the people hate it. They feel it is above them and they hate it all the worse". Pennell also reiterated his belief that 'natives in that part of England' like to 'eave 'arf a brick at the furiner', and the foreigner is anyone they do not know'[11]

The work was successfully published as Lithographs of War, bringing acclaim and an invitation from the French Minister of Munitions to portray the war in France. Aided by Henry Durand-Davray, Pennell obtained a Govt. permit to visit Verdun and illustrate the war at the front, travelling to France as part of a Press corp. But Pennell found it too horrific to stay; as a peaceful Quaker he loathed the destruction wrought by war and, finding the scenes in France unbearable, he quickly left. 'Owing to a combination of unfortunate circumstances, the artist, to his own great regret, found himself, as he confesses unable to make any pictorial record of what he saw there'.[21] Pennell later wrote in Adventures of an Illustrator;

I had had my sight of War and felt and knew the wreck and ruin of War, the wreck of my life and my home-and that has never left me since.[2]

Pennell returned to England from the aborted French assignment, then onto America with wife Elizabeth. When the United States entered the war in April 1917, Pennell was authorised to make records of the US war effort similar to those undertaken in England; In The Dry Dock, 1917[22] The Transports 1917[23] He also produced official posters for the Division of Pictorial Publicity, formed to aid the US war effort – That Liberty Shall not Perish.. 1917.[24] Provide the Sinews of War Buy Liberty Bonds, 1918.[25]

Pennell commented on the relationship of government to the arts at the time; "When the United States wished to make public its wants, whether of men or money, it found that art–as the European countries had found – was the best medium."[26]

Return to America and final years

[edit]Pennell returned to England, from the aborted 1916 French war assignment, then onto America with wife Elizabeth, where he was authorised by the U.S. Government to make records of their war effort, similar to as he had undertaken in England; In The Dry Dock, 1917[22] The Pennells spent time in Philadelphia but didn't settle; Joseph traveled, lectured, and worked in Washington, D.C. organising the Pennell's Whistler collection, bequeathed to the Library of Congress in 1917 (The papers remained in storage in London until the end of the War) and in 1921 the couple moved to Brooklyn, New York.

In 1925, Pennell published The Adventures of an Illustrator, now available as a free e-book:[27] Pennell was working as a teacher at the Art Students League up until a week before his death. Among his students was Frances Farrand Dodge. He contracted influenza, which developed into pneumonia, and died at home in the Hotel Margaret, Brooklyn Heights on April 23, 1926.

In his 1951 biography of the Pennells, Edward Larocque Tinker stated that:"

[J]ust before he (Pennell) died he begged to be carried to his window for one last look at the view of Manhattan that he loved and had often sketched and painted. The doctor thought it unwise, but I have always regretted that Mr. Pennell was deprived of this last pleasure.[2]

Upon his death Pennell bequeathed his own prints, papers, and estate to the Library of Congress, subject to provision made for Elizabeth's use of the estate until she died. Elizabeth was the guardian of the couple's estate, on her death it was bequeathed to The Library of Congress, while her personal letters were given to friends, and later to the University of Pennsylvania and University of Texas.

Miscellaneous

[edit]

He wrote and illustrated a travel book, The Jew at Home: Impressions of a Summer and Autumn Spent with Him (D. Appleton: New York, 1892), based on his travels in Europe.[28][29] According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, while professing to be neither a Jew hater or Jew lover, the portrait he portrays is "extremely unflattering" and the book is part of the museum's Katz Ehrenthal Collection of antisemitic artifacts and visual materials.[28] He produced other books, many of them in collaboration with his wife, Elizabeth Robins Pennell.[15]

Pennell designed the poster for the fourth Liberty Loans campaign of 1918. It showed the entrance to New York Harbor under aerial and naval bombardment, with the Statue of Liberty partly destroyed.[30]

Mount Pennell in Utah was named after him.[31]

Little Wakefield

[edit]In 1880, Pennell created Little Wakefield, an etching of the Little Wakefield estate.[32] The building is a home located on what is now South Campus of La Salle University, and is currently called St. Mutiens hall. This estate was built by Thomas Fisher in 1829 and was occupied by his families for generations; now it is the residence of the Christian Brothers of the university.[33] The etching depicts the house lived in by the second generation of Fishers. During World War I it was used as demonstration center for a local branch of the National League of Women's Service. Little Wakefield was also the location where Thomas R. Fisher ran the first knitting factory in America.[34]

Personal life

[edit]Pennell; married Elizabeth Robins Pennell, a writer and fellow Philadelphian, on June 4, 1884. 'A marriage of equals and complements, bringing together two talented individuals with keen minds, ambition, and a love of work.'[35] They had a mutual agreement to not let their marriage interfere with their work. As Elizabeth later wrote:

After Canterbury [the publication of their first book, A Canterbury Pilgrimage in 1885] the opportunity came to test the resolution reached before our marriage, not to allow anything to interfere with his drawing and my writing. Should they call us in different directions, each must go his or her way.[35]

The Pennells co-authored books about their travels abroad together, and while apart working, wrote many letters to each other, now kept by the University of Pennsylvania and University of Texas.[2] After Joseph's death in 1926, Elizabeth was guardian of their estate, until it passed to the Library of Congress upon her death in 1936.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Joseph Pennell, Noted Artist, Dead; Won High Honors as Etcher and Illustrator, Later Taught Art and Wrote Books" (PDF). The New York Times. April 24, 1926. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Pennell family papers, circa 1882-1951". Dla.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b c Graves Gallery. "The Wonder of Work: Prints of War & Industry by Joseph Pennell". Museums Sheffield. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b c "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Joseph Pennell's Pictures of the Wonder of Work, by Joseph Pennell". 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2021-01-26 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b rebecca.m. "The adventures of an illustrator, mostly in following his authors in America & Europe : Pennell, Joseph, 1857-1926. cn : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b Young, Mahonri Sharp (1970). "The Remarkable Joseph Pennell". American Art Journal. 2 (1): 81–91. doi:10.2307/1593868. JSTOR 1593868 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Bearden, Romare (1993). A history of African-American artists : from 1792 to the present. Harry Henderson. New York. pp. xi. ISBN 0-394-57016-2. OCLC 25368962.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Artist Info". nga.gov.

- ^ "Bethlehem Steel Works". Loc.gov. 1881. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b Pennell, Joseph (February 3, 1925). "The adventures of an illustrator, mostly in following his authors in America & Europe". Boston, Mass., Little, Brown and Company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c "The Opinionated Joseph Pennell (1857-1926)". Victorianweb.org. 2015-11-15. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "Picture". Retrieved 2021-01-26 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Joseph Pennell's Pictures of the Wonder of Work, by Joseph Pennell". 2018-08-08. Retrieved 2021-01-26 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Česky. "The Big Chimney, Sheffield – Joseph Pennell – WikiGallery.org, the largest gallery in the world". Wikigallery.org. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b c One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pennell, Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b Margaret J. Schmitz (2016-10-05). "Joseph Pennell and the Anglo-American Construction of New York – Tate Papers". Tate. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ Mary Millman and Dave Bohn, authors of The Master of Line: John W. Winkler, American Etcher , (Capra Press: Santa Barbara, CA, 1994).

- ^ a b "Steam Shovel in the Cut at Bas Obispo". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ Adams, Clinton (1983). American lithographers 1900-1960. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. p. 19. ISBN 0826306608.

- ^ "From the Tops of the Furnaces – Joseph Pennell, American, active England, 1857–1926 – Google Arts & Culture". Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "Data". artic.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b "In the Dry Dock". nga.gov. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "The Transports – Joseph Pennell – Google Arts & Culture". Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "That Liberty Shall Not Perish from the Earth, Buy Liberty Bonds | Smithsonian American Art Museum". Americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "Provide the Sinews of War-Buy Liberty Bonds. – Fourth Liberty Loan, Fourth Liberty Loan (sponsoring program), and Pennell, Joseph, 1857-1926 – Google Arts & Culture". Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ "Joseph Pennell | Smithsonian American Art Museum". Americanart.si.edu. 1926-04-23. Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ rebecca.m. "The adventures of an illustrator, mostly in following his authors in America & Europe : Pennell, Joseph, 1857-1926. cn : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 2021-01-26.

- ^ a b "Accession Number: 2016.184.228". collections.ushmm.org. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

- ^ Pennell, Joseph, The Jew at Home (NY, 1892), https://archive.org/details/cu31924028574352

- ^ "Lest Liberty Perish from the Face of the Earth – Buy Bonds". World Digital Library. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ Pete Klocki and Tiffany Mapel, A Wild Redhead Tamed: A Brief History of the Colorado River and Lake Powell, 2009, page 86.

- ^ "Pennell family papers, circa 1882-1951". dla.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ^ "Welcome to the La Salle Local History Web Page". lasalle.edu. Archived from the original on 2001-05-26. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ^ "Welcome to the La Salle Local History Web Page". lasalle.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-10-26. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ^ a b "Pennell family papers, circa 1882-1951". dla.library.upenn.edu.

External links

[edit]- Works by Joseph Pennell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Joseph Pennell at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Joseph Pennell at the Internet Archive

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on Joseph Pennell.

- Joseph and Elizabeth R. Pennell's papers at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin

- Joseph Pennell: an account by his wife, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, issued on the occasion of a memorial exhibition of his works, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF)

- Finding aid for the Pennell family papers from the University of Pennsylvania Libraries